History of Parliamentarism in BiH

Political representation of BiH in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes/Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1918 – 1941)

As of 1914, there were no institutional activities by the Bosnian Council, the legitimate representative body in making decisions on the future status of Bosnia and Herzegovina. There were various opinions, ranging from those on the establishment of autonomy of Bosnia and Herzegovina within Hungary, to its union with Croatia, to the acceptance of the solutions contained in the May and Corfu Declarations.

(Monographs of the "Parliamentary Assembly of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the 2010 edition.)

The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (SCS), which also included Bosnia and Herzegovina, was established on December 1, 1918 following World War I and the defeat of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. During the process of unification, at the initiative of the Yugoslav caucus, a Resolution on the Unification of Yugoslav Peoples who had been parts of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy was issued in Zagreb on March 2 and 3, 1918. The meeting was also attended by representatives of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It was proposed on that occasion that the National Council of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs (SCS) be established with its seat in Zagreb, where the political parties and national organizations of South-Slav peoples from the Austro-Hungarian monarchy were represented. The National Council of SCS, as the supreme body of the new state, was established on October 5 and 6, 1918 and was tasked with preparing the unification of all South-Slav peoples and with setting up the state on a democratic basis. It counted 80 members, of whom 18 were from Bosnia and Herzegovina, plus additional five members from the abolished Bosnian Council. The Central Board consisted of 36 members, of whom six, along with two deputies, were from Bosnia and Herzegovina, though there were no Muslim representatives.

The National Council of SCS for Bosnia and Herzegovina, along with its Main Board, consisted of 25 members and a 5 member Presidency, and was formed on October 20, 1918 and comprised representatives of all three peoples. By November 1, 1918, the police and armed forces had been established, including District, Regional and Rural Boards, and the Austro-Hungarian monarchy handed power over to this Council on the same day with the resignation of the governor Sarkotić. The first national government of Bosnia and Herzegovina was established on November 3, 1918 and comprised 10 members, of whom the President and five Ministers (or commissioners) were Serbs, three members were Croats and one member was Muslim. Atanasije Šola was the President of the Government.

Banski dvor, the cultural centre of Banja Luka, was built in the period between 1929-1932 as the seat of Ban (Viceroy) of Vrbaska banovina (Province of Vrbas) in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

The Government of the National Council of SCS for Bosnia and Herzegovina functioned from November 1, 1918 to January 31, 1919, when it was replaced by the National Government for Bosnia and Herzegovina on February 1, 1919, which became the supreme administrative body over all administrative-territorial bodies in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Organizational changes in the structure of the National Government of Bosnia and Herzegovina were very frequent and adjusted to the state government. It was comprised of eight committees chaired by the President Atanasije Šola. On July 11, 1921, the National Government was replaced by the Regional Administration of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

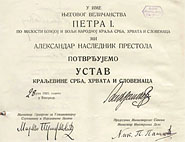

Bosnia and Herzegovina became part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes by an inauguration address of the National Council of SCS delivered to the regent Alexander which he, on behalf of his majesty King Peter I, received on December 1, 1918 in Belgrade. Although the delegation of 28 members, seven of whom were from Bosnia and Herzegovina, received clear instructions on the conditions and modalities of unification on a democratic basis, by the act of December 1 the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs was unified with Serbia into one state under the name the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (SCS). On December 3, 1918, the Presidency of the National Council of SCS declared that the act of uniting ceased the functioning of the National Council, being the sovereign representative body of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. The first common government of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was established on December 20, 1918, including Tugomir Alaupović, Ph.D., Mehmed Spaho, Ph.D., and Uroš Krulj, Ph.D., from Bosnia and Herzegovina. By this act of unification, the previously agreed upon procedures for the union of two states was abandoned, although they were agreed upon during the trilateral negotiations held in Geneva from November 6-9, 1918, on which occasion the Serbian Government was represented by Nikola Pašić, the National Council of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs by Anton Korošec, and the Yugoslav Committee by Ante Trumbić, the abandonment of which was the reason for the ongoing crisis during the existence of the Kingdom of SCS/Yugoslavia. Thus, instead of a state organized on a federal principle, a centralized monarchy with a strong unitary government and single national political representation was established. Under such circumstances, Bosnia and Herzegovina and its historical heritage became a part of Yugoslavia.

By the act of uniting and the establishment of the central government in Belgrade, the preparations for the elections for the first Constituent Assembly of the Kingdom of SCS commenced, which was not convened immediately after the proclamation of the union as there was no election law in place. By the decree of February 24, 1919, the central government decided for the Interim Assembly to have 296 members, provided that all parties and political groups were represented proportional to their number in every individual province. The National Council of Bosnia and Herzegovina elected 42 members from the parties represented on the Council. By the end of September 1920, the National Council ceased functioning and all powers in Bosnia and Herzegovina passed to the central government in Belgrade. The Interim Assembly scheduled the elections for November 28, 1920. The 63 representative seats assigned to Bosnia and Herzegovina were won by the following: the Yugoslav Muslim Party (24), Association of Peasants (12), National Radical Party (11), Croatian Labour Party (7), Communist Party of Yugoslavia (4), Croatian Popular Party (3) and Democratic Party (2). After the election statistics were publicized, protests came from all sides and discontent was manifested immediately after the first convocation of the Constituent Assembly of the Kingdom of SCS on December 12, 1920. Of the 419 elected representatives, 342 representatives delivered their credentials to the Verification Board, while the representatives of the Croatian Popular Party and the Croatian Party of Rights did not even attend the first session, nor were there 10 representatives from the part of the country under Italian occupation. Therefore, political tensions were already pronounced. Pursuant to Article 140 of the St. Vitus’ Day Constitution which was adopted on June 28, 1921, the Constituent Assembly became legislative on June 29, 1921.

The decree on the division of the Kingdom of SCS into 33 regions was issued in 1922 by the government, while the political deal of Mehmed Spaho, Ph.D., leader of the Yugoslav Muslim Organization, with the radical-democratic government concerning the St. Vitus’ Day Constitution enabled Bosnia and Herzegovina to keep its territorial integrity within its current borders. Thus, according to the new Constitution, six districts from the period of Austro-Hungarian rule were renamed as six regions: Bihać, Mostar, Sarajevo, Travnik, Tuzla and Vrbas. The new Election Law was enacted on June 21, 1922, and with certain amendments it remained in force until the establishment of the January 6 Dictatorship. The St. Vitus’ Day Constitution did not guarantee women the right to vote. A passive right to vote belonged to candidates older than 30 years of age. Active military officers and soldiers did not have the right to vote, and communists were deprived of the passive right to vote. A thorough analysis of the Election Law indicates that it was intended for strengthening central authorities, which is particularly evident in the election method applied in the one-seat election regions.

At the Assembly elections on March 18, 1923, February 8, 1925 and special elections for national representatives of the Kingdom of SCS held on September 11, 1927, the most seats in Bosnia and Herzegovina were won by the following: the Yugoslav Muslim Organization, the National Radical Party, and the Croatian Republican Peasant Party. The religious-national affiliation of voters reflected the election results brought into the Assembly of the Kingdom of SCS as well as the tensions and misunderstandings that culminated in the assassination of the representative of the Croatian Peasant Party, which caused King Alexander to set up a dictatorship on January 6, 1929, abolish the Constitution, dissolve the Assembly and ban the work of all political parties. In October 1929, the King enacted the Law on Renaming the Kingdom of SCS the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and its division into administrative regions. Internal reorganization resulted in the establishment of nine banovinas and the Administration of the City of Belgrade as the tenth administrative unit. Like the other Yugoslav countries, through this division Bosnia and Herzegovina also lost its historically unique territorial integrity and was split into four banovinas: Vrbas, Zeta, Primorje (trans. Littoral) and Drina. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the administrative centres of two banovinas were Sarajevo of the Drina banovina and Banja Luka of the Vrbas banovina, while its two remaining banovinas were centered outside Bosnia and Herzegovina - Primorje in Split and Zeta in Cetinje. This considerably affected the ethnic structure of the population, as in the banovinas of Vrbas and Drina, the majority population were Serbs, in Zeta Serbs and Montenegrins, and in Primorje Croats. The divisions made Muslims a minority in all of the four banovinas. King Alexander centralized the administration and intended to use the new division to resolve the national issue by imposing an integral Yugoslavism wherein, instead of three peoples in Yugoslavia, there existed only one Yugoslav people of three tribes (Serbian, Croatian and Slovenian). Having abolished all of the democratic characteristics of the Yugoslav state-political system, the King proclaimed the Law on the Power of the King and Supreme State Administration, thus assuming both legislative and executive power.

In the summer of 1931 it was announced that the parliamentary system would be restored. King Alexander enacted a new Constitution of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (the Octroyed Constitution) on September 3, 1931, thus restoring parliamentarism, though not a parliamentary system in a democratic sense. The new Constitution introduced a bicameral Assembly – the National Assembly and the Senate, by which the King attempted to change the form but not the essence of absolute rule. The Octroyed Constitution established the out-of-parliamentary government system − the government did not stem from the parliamentary majority and did not report to the Assembly but rather to the King, who appointed and relieved of duty the President of the Council of Ministers and the Ministers themselves. By the King’s Decree of September 23, 1931, the elections were scheduled for November 8, 1931, while the newly elected Assembly was to meet the same year on December 7 in Belgrade. Candidature covering the whole country was planned for the elections under the “national candidate list” and no candidature was allowed in smaller election precincts. In accordance with the amendment to the new Election Law, secret voting was abolished and an open vote was introduced. The 1931 Election Law and its by-laws served to strengthen centralism and integral Yugoslavism in a national sense, and to strengthen the King’s powers as well. In the context of these elections, it is not possible to talk of Bosnia and Herzegovina because of the administrative system which had divided it into banovinas. This Assembly functioned directly under the influence of the Court, in accordance with the January 6 dictatorship and the Octroyed Constitution, achieving its plan of tearing apart historical and national territories. The King’s power did not give way after the amendments to the Election Law of March 24, 1933 which increased the number of representatives increased to 370, but had little effect on the king’s tendency to retain centralism.

The king’s attempts to hide his absolutist rule failed, as there followed ample protest letters (orig. punktacija) expressing dissatisfaction. The demands of the November 7, 1932 Resolution by the Peasant-Democratic Coalition, which comprised the Croatian Peasant Party and the Independent Democratic Association, better known as the “Zagreb’’ and “Maček’’ protest letters, which called for the abolition of Serbian predominance in the Kingdom, triggered the reactions of the Democratic Party which, in January 1933, published “A Letter to Friends’’ known as “Davidović’s protest letters” requesting the state be reorganized so that it consisted of four federal units of which Bosnia and Herzegovina would be one. Mehmed Spaho, Ph.D., leader of the Yugoslav Muslim Organization, also took this view and, through the “Sarajevo protest letters”, he criticized the centralist system and demanded that the equality of historical-political units, including Bosnia and Herzegovina as a non-discriminated member, be respected.

The assassination of King Alexander in Marseille, France, in 1934 and the appointment of a three-member regency headed by Prince Pavle Karađorđević instigated elections on May 5, 1935, which included two election groups: a National list including Bogoljub Jeftićem, and the list of the United Opposition headed by Vlatko Maček. The opposition program parties joined the United Opposition: the Peasant-Democratic Coalition, the Yugoslav Muslim Organization, Davidović’s wing of the Democratic Party and a part of the Farming Party. The appearance of Vlatko Maček undoubtedly indicated the tendency to open the “Croatian Issue” in the Kingdom. The elections were won by the list of Bogoljub Jeftić with 60.6% of the vote and 303 seats, while the list of the United Opposition won 37.4% of the vote and 167 representative seats. However much the victory of the government list was celebrated, it meant the continuation of terror against persons of different views, communists and federalists in particular.

Again, there were requests for the autonomy of Bosnia and Herzegovina after these elections. Apart from the foregoing political parties, the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, which acted underground, indirectly expressed its position. Stimulated by these ideas, Bosnia and Herzegovina youth who studied in Belgrade, Ljubljana and Zagreb published three letters: in December 1937, March 1938 and December 1 1939, in which they pointed out the special characteristics of Bosnia and Herzegovina as a political, economic, cultural and historical whole. However, these requests had no effect.

The regency headed by Prince Pavle dissolved the Assembly and announced new elections to be held on December 11, 1938. These were the last elections for the National Assembly in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. The Election Law already gave preference to the Government List, which fully won through various forms of election rigging. In early February 1939, the regent, Prince Pavle, entrusted the Government to Dragiša Cvetković and empowered him to reach an agreement with Vlatko Maček, leader of the Croatian Peasant Party. The period of time following the December elections was full of uncertainty and tension in Yugoslavia, mirroring the international political sphere. The parliamentary crisis could not be overcome, the Assembly discontinued its work and all legislative and executive power passed on to the regency, that is, Prince Pavle and the Government.

There was an attempt to resolve the issue of the state-political system of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia by the Cvetković-Maček Agreement signed on August 26, 1939. This Serbian-Croatian agreement had parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina become parts of a newly established Autonomous Banovina of Croatia, which now included the following territories of Bosnia and Herzegovina: in the Sava River basin (orig. Posavina) – the municipalities and counties of Brčko, Gradačac, Bosanski Šamac, Bosanski Brod and Derventa, and in southwest Bosnia and Herzegovina: Stolac, Čapljina, Ljubuški, Mostar, Konjic, Prozor, Fojnica, Travnik, Bugojno, Tomislavgrad and Livno. According to the Agreement, the remaining part of Bosnia and Herzegovina was to be a part of the projected community of Serbian Countries (orig. “Srpske zemlje”). However, no one was satisfied with the Agreement as it could not result in the consolidation of a political situation overloaded with social and ethnic problems. Amid this situation, the Yugoslav Muslim Organization requested that Bosnia and Herzegovina should be established within its historical borders with Sarajevo as its center. After Mehmed Spaho, Ph.D. died in 1939, the Party was taken over by Džafer Kulenović, Ph.D. who proposed the foundation of the fourth “Banovina of Bosnia.” The movement for autonomy was established on December 30, 1939 and its Executive Board sent out a circular to all Muslim organizations and associations in the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina to set up local boards with the aim of achieving the autonomy of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which process was interrupted by World War II.

The last Government of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, the Government of Dragiša Cvetković and Vlatko Maček, fell on March 27, 1941. After the Kingdom of Yugoslavia signed a document to join the Tripartite Pact on March 25, 1941 and the demonstrations two days later, Hitler’s air force attacked Belgrade, the royal army was quickly defeated, the king and the government went into exile, and the country was occupied by fascists and torn apart, all leading to the end of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

From the establishment of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia to the collapse of all of its segments, the political representation of Bosnia and Herzegovina was characterized by continued disruptions, political instability and differences on fundamental issues that remained unresolved from 1918 onwards. Apart from the basic conflict between the centralization and federalization of the country, Bosnia and Herzegovina had to take permanent care to preserve its territorial integrity. The leading parliamentary political parties from Bosnia and Herzegovina acted on a religious-ethnic basis. In addition, the Serbian and Croatian parties had their respective headquarters in Belgrade and Zagreb, and therefore could not truly represent the interests of the population of Bosnia and Herzegovina in its entirety. The attempts to set up parliamentarism, the prohibition of left-oriented political parties, the introduction of dictatorship and an accumulation of social and ethnic problems, along with the beginning of World War II and the revolutionary-liberation war, all provided the conditions for changes to the political system and political representation..